Linguistic Implications of Attention-Based Models

In the article Deep Learning in Semantics Chris Potts argues that the role of deep learning (DL) techniques in linguistic semantics extends beyond purely empirical methods by formalizing a semantic theory grounded in DL (Potts, 2019). This article builds on top of Potts’ work to explore the role of contextual word representations in lexical semantics. First, this article provides a summary of Potts’ DL semantic theory. Then, the article provides the relevant description of contextualized word representations and compares them to the static word representations discussed in (Potts 2019). Finally, this article concludes with limitations of DL semantic theory in the light of contextualized word embeddings and their implications to lexical semantics.

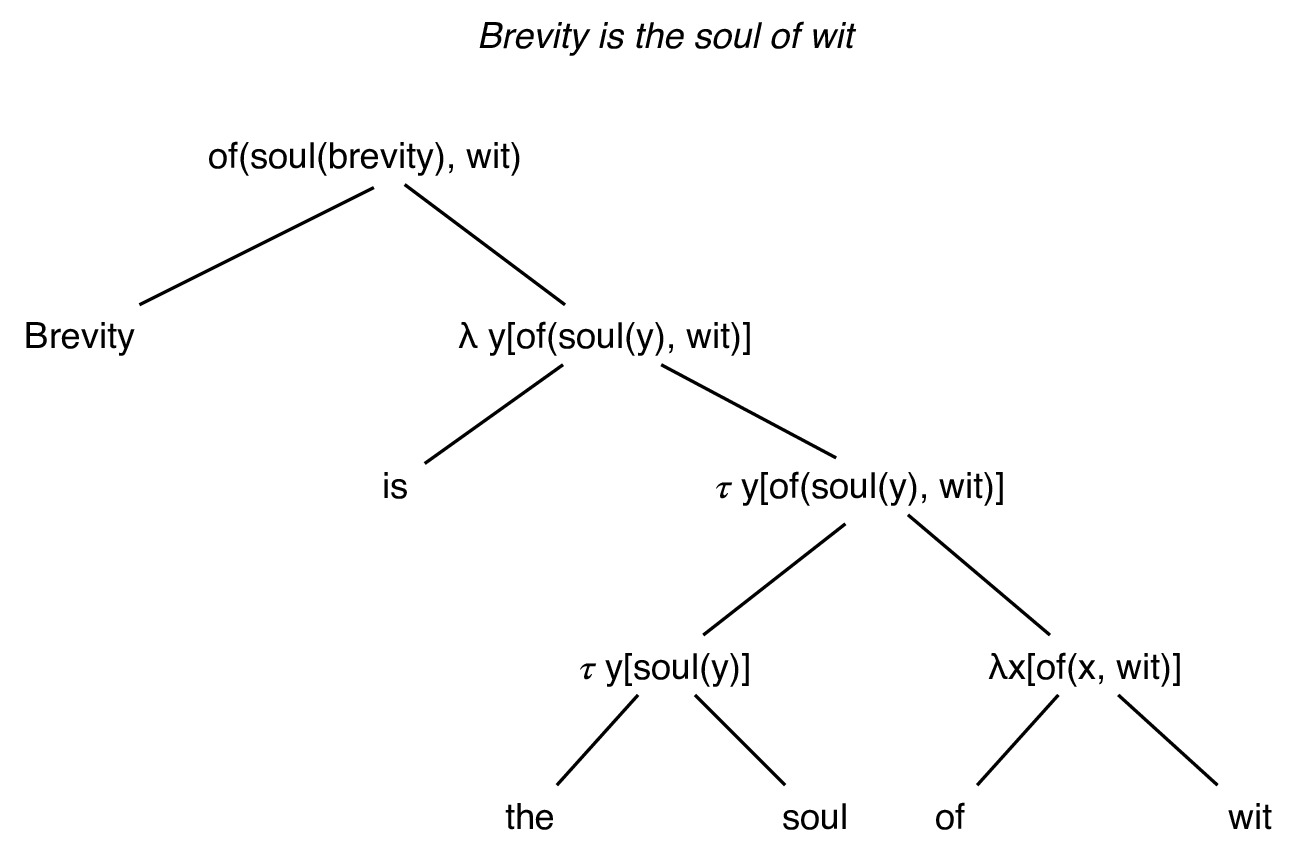

According to the principle of compositionality, the meaning of a sentence is determined by the composition of its parts (Geach and Black, 1990). Normally, the composition is functionally performed on logical variables (as can be seen in figure 1). However, (Potts 2019) defines compositionality using linear algebra. Chris Potts creates a DL semantic theory by defining lexemes as word vector representations and semantic composition as linear algebra operations on word vectors or their linear compositions. Importantly, by drawing a parallel between lexical entities and word vector representations, Potts considers word vectors as discrete (lexical) entities. Such an assumption is fair for static word vector representations, where there exists a discrete, context-independent mapping between words and their tensor representations. However, it is interesting to reconsider the said assumption in the light of contextual word embeddings.

Word vector representations are used to quantitatively represent semantics so that operations on the word vector correspond to the semantics of the word. For example, word vectors representing semantically similar terms have a higher cosine similarity than those representing semantically different words. Until recently the most common word vector representations were static — they would map a term to its vector representation regardless of the context (Pennington et al. 2014) (Mikolov et al. 2013). The static property introduces a number of limitations, most importantly problems with polysemy (Ethayarajh, 2019). Recently introduced, contextualized vectors solve this problem by taking into account the term’s context in its representations (Vaswani et al. 2017).

The contextual dependency of word vectors violates the compositional tree relationship illustrated in figure 1. In other words, the meaning of the sentence is no longer simply a composition of individual word meanings since said meanings are a function of the sentence (context).

Let us consider the implications of contextualized word vectors on lexical semantics. On the one hand, we can persist with the compositional semantic theory, justifying the contextualized construction of the individual meanings as a statistical tool for representing polysemy. On the other hand, contextualized word vectors can motive the necessity for a continuous semantic theory.

The evidence for the latter argument consists of the resonance between continuous semantics theory in linguistics (Fuchs and Victorri, 1994) and the empirical observations of contextualized word embeddings (Ethayarajh, 2019). Namely, (Fuchs and Victorri, 1994) hypothesize that the meaning of the word in a context of utterance consists of a continuous combination of senses, producing an infinite number of similar meanings. Likewise, the results of (Ethayarajh, 2019) demonstrate that layers of the model have varying sensitivity to context and the resultant empirical model produces an infinite set of meanings for each lexical entity.

To conclude, this article demonstrates how considering statistical machine learning methods within a theoretical linguistics framework provides the empirical feasibility of said frameworks. In particular, Chris Potts’ DL semantics theory, demonstrates the practicality of discrete compositional semantic theory, through the performance of static word vector deep learning models. Likewise, the recent state of the art performance of contextualized word representations highlights the limitations of discrete semantics and emphasizes the necessity of continuous lexical semantics.

Works Cited

Ethayarajh, K. “How Contextual are Contextualized Word Representations? Comparing the Geometry of BERT, ELMo, and GPT-2 Embeddings.” Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 2019.

Fuchs, C. and Victorri, B. Continuity in linguistic semantics,Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co., pp.230-241, 1994.

Geach, P. and Black, M. Translations from the Philosophical Writings of Gottlob Frege, Oxford: Blackwell, third edition, 1966.

Mikolov, Tomas, et al. “Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26 (NIPS 2013), 2013.

Pennington, Jeffrey, et al. “Glove: Global Vectors for Word Representation.” Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2014, doi:10.3115/v1/d14-1162.

Potts, C. “A Case for Deep Learning in semantics: Response to Pater”. Language, 2019.

Vaswani, Ashish, et al. “Attention Is All You Need.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 31 (NIPS 2017), 2017.